C Z GUEST

Flip through the "inspiration" file that every designer keeps, and at some point you will find a picture of C.Z. Guest. Debutante, showgirl (briefly), model (painted nude by Diego Rivera), socialite, gardener, intimate of artists and writers; Guest had the kind of life that seems fiction, and the perfect patrician looks to illustrate it. She wore her designer clothes with thoroughbred elegance, keeping to simple lines, rich fabrics, and soft colors to suit her cool complexion. But perhaps what drew creative types to her most was Guest's down-to-earth personality, exemplified by her recent advice to would-be gardeners visiting her web site, "The most important thing is to enjoy yourself and have a good time."

Comments

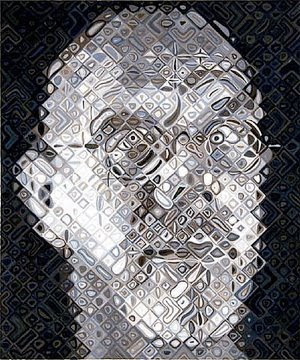

"I have never wanted to paint anything else," said Close at the opening of an important retrospective of his work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York at the end of February.

New York is Close territory. He moved to the city in 1967 along with a group of artists of his generation that had been in his class at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., such as Richard Serra, Nancy Graves, and Brice Marden.

Close, who photographs his subjects and then works from the print, uses people close to him as his subjects - his family, friends, and colleagues. The MOMA exhibition, which begins and ends with a self-portrait, is arranged in chronological order.

It leads one through 17 years and 90 examples of Close's work, including people he was involved with in the New York art world. From his first works in gray and white to the painterly, colorful oils of the '90s, Close's faces stare out of their oversized canvases in an eerie way. The more recent portraits remind one of images frozen on a color television.

Close's world is one of meticulous technique and unwavering hard work.

All the paintings are done on grids, his work built from units. As Close says, this structural approach to a painting is a product of his nature: "I really need to break things down to a manageable and solvable problem. My work has always been driven by self-imposed limitations."

This constancy and the fact that Close has never strayed from the path of portraiture led a critic who has been following his work since the '70s to remark recently that the artist's work still "breathes the air of pictorial tedium."

But Close's work is highly popular as well. Explained in his own words: "We all share a common knowledge and interest in faces. We all care a lot about faces." The oversized heads, with occasionally bulging eyes, stare out of their canvases with a sort of detached presence, which remains constant as one follows the transitions in technique. The show's curator, Robert Storr, speaks of Close's paintings as having a literal texture, a skin of their own; in some, it is finger-painting over the painter's grandmother-in-law's or composer Philip Glass's face, in others, a symmetrical pointillism.

A serious illness in late 1988 and his return to painting produced portraits that are far more colorful and looser than his former work. Close said in a recent interview in The New York Times Magazine: "My new portraits have a celebratory aspect that wasn't there before ... because I feel so happy that I was able to get back to work."

Once one accepts the repetition and overwhelming painstaking technique, Close's more recent work especially draws the viewer into his kaleidoscopic world of portraits.